What Makes an Adult? | Psychology Today

In Western societies, adulthood has been traditionally measured by socio-demographic milestones such as having a stable job, buying a house, getting married, and having children. But today, there are reduced opportunities to attain these milestones as young people spend extended periods of time in education, are financially dependent on their parents for longer, and struggle to afford to buy their own flat or house. Young people today are also more likely to delay getting married and having kids compared with previous generations.

These trends are documented by demographic data. For example, the number of marriages occurring in England and Wales has halved between 1972 and 2020. Today, people wait until their early 30s to get married for the first time, but in the 1970s, they said “I do” at an average age of 23. The average age at which women have their first child has also risen by almost a decade, from 24 in the 1960s to 31 in 2021. These trends are not unique to the UK—patterns of less frequent and later marriage and childbirth have been observed in many other countries, including the U.S., Sweden, Japan, and Chile.

Many of the psychological models that we use to measure development were built in the 1960s, which was a time of economic prosperity when young people tended to get married, buy a house, settle into a stable job, and have children in quick succession in their early 20s. The traditional socio-demographic milestones of adulthood were more affordable and happened earlier.

Since the 1960s, pathways to adulthood have dramatically changed, so we need to redefine what it means to be an adult in the 21st century. Instead of defining adulthood as a collection of socio-demographic milestones, we should consider adulthood as a time of continuous development defined by individual psychological characteristics.

To see whether the traditional socio-demographic milestones of adulthood are still important for adult status today, we surveyed 722 UK residents aged 18-77 years. Our study, currently a preprint, assessed when people feel like adults, why they feel like adults, and whether they see adulthood as a positive or a negative time of life.

When Do People Feel Like Adults?

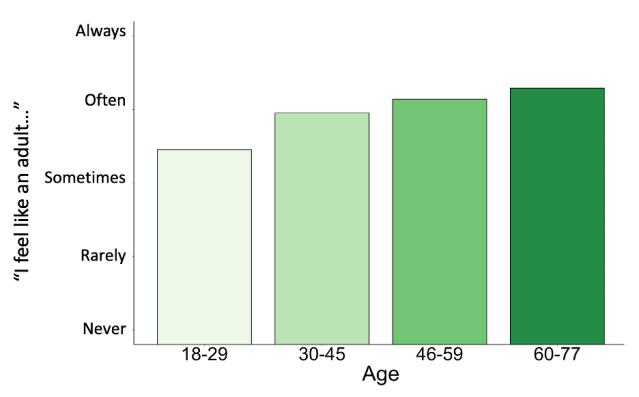

We found that the average age when people start to feel like an adult is 25. As one would expect, older participants were more likely to feel like adults, and the youngest participants in our study, who were 18 years old and legally considered adults, were the least likely to call themselves adults. But, while older people felt more grown-up on average, even our oldest age group—those aged 60 to 77 years—reported that they still didn’t feel like an adult all the time.

Participants in our study were asked to complete the sentence “I feel like an adult…” with one of the following responses: “always,” “often,” “sometimes,” “rarely,” or “never.” This graph shows participants’ average responses across age groups from 18-29 years up to 60-77 years old.

Source: Megan Wright

Why Do People Feel Like Adults?

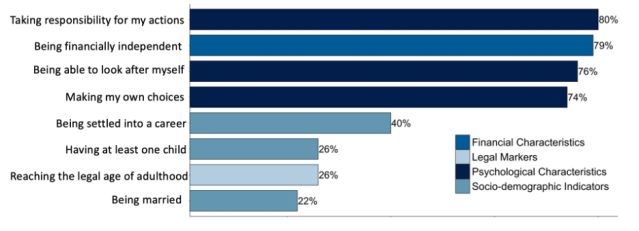

To measure why people feel like adults, we presented our participants with 47 characteristics of adulthood based on previous research and asked them to rate whether or not these characteristics were important for adult status. Adulthood characteristics included socio-demographic milestones, such as marriage and parenthood; legal markers of adult status, such as the age of majority, which is 18 in the UK; and psychological markers of adulthood, such as “taking responsibility for the consequences of my actions” and “being able to look after myself.”

Psychological characteristics were considered much more important for being an adult compared with the traditional milestones like marriage and parenthood or the legal markers of adulthood, such as reaching age 18.

The percentage of participants who agreed that these characteristics made someone an adult. One hundred percent would indicate agree, and 0 percent would indicate disagree. Participants agreed that psychological characteristics, in dark blue, defined adulthood much more than socio-demographic milestones or legal markers of adulthood, both in lighter blue on the graph.

Source: Megan Wright

How Do People Feel About Adulthood?

We also asked whether our participants saw adulthood as a positive or negative time of life by measuring their attitudes toward adulthood.

We found that participants aged 60 and above had the most positive attitudes towards adulthood in our study, and they agreed with the statements “adulthood is a desirable time of life” and “I enjoy being an adult.” Participants aged between age 18 and 29 in our study held the most negative views, and they thought that adulthood was “an undesirable time of life” and agreed with the statement, “I do not enjoy being an adult.” In our study, 60-77-year-olds’ attitudes towards adulthood were 25 percent more positive than those of 18-29-year-olds.

Age 18-29 represents a special point in adult development and has been termed emerging adulthood, a time of life associated with feelings of instability, uncertainty, and exploration. Emerging adults may struggle with or resist the transition to adulthood because they don’t feel that they belong in the adult population. One recent study found that having a “sense of adulthood,” or feeling like an adult, led to better well-being. Therefore, the way we feel about our own adult status could impact our happiness.

In our study, attitudes towards adulthood predicted adult status, meaning that people who had more positive attitudes about adulthood were more likely to think of themselves as adults, no matter what age or gender they were. This relationship between positive attitudes toward adulthood and feeling like an adult was present in people who were married or unmarried and who had five children or no children. This suggests that if people think that adulthood is a positive time of life, they will be more likely to feel like an adult.

This finding is key because attitudes toward adulthood are malleable—in other words, they can be changed. Our study suggests that fostering positive attitudes toward adulthood could increase people’s own adult status. If future research confirms that subjective adult status is associated with well-being, attitudes toward adulthood could be used in interventions to improve young people’s subjective adult status and, in turn, their well-being.

So, What Makes an Adult?

Research shows that adulthood is more than the socio-demographic labels of employee, spouse, and parent—it is a rich, dynamic, and rewarding phase of life defined by continuous psychological change. And feeling grown-up—whatever that means for you—could have a positive impact on your well-being.